Maui Hikina is famous for its abundant fields of lo’i kalo (wetland taro) that provided healthy food for residents, habitat for native stream life, and buffers from flash flooding.

ʻOiʻoi ‘o Maui Hikina – Maui Hikina forges ahead. This saying heralds the resilience and independence of this renowned community, which has resisted the decimation of its wai and practices under the totemic traditions of moʻo – sacred reptilian water deities – since time immemorial. Communities in the northeast region of Maui, known as Maui Hikina, have revered and safeguarded their stream and groundwater resources, as reflected in totemic traditions of mo‘o (legendary reptilian water deities), as well as customary laws governing the management of water.

Maui Hikina was historically renowned for its fully self-sustaining economy, equal to or greater than any other wetland kalo (taro) growing landscapes in Hawai‘i nei.

Sugar cane plantation circa 1870, required a lot of hard labor and diverted stream water. Photo credit: Alexander & Baldwin

In the late 1800s, with the introduction of sugar in central Maui and the construction of large-scale ditch systems, agreements for plantation water diversions still gave highest priority to the rights of Maui Hikina’s wetland kalo farmers and other downstream users. Following the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom in 1893 by commercial sugar interests with the support of the U.S. military, these agreements unraveled. The sugar barons profited off their massive water diversions, while Native Hawaiian ‘ohana (families) from Maui Hikina moved away or adjusted to life drained of water.

Over decades, officials charged with protecting Hawai’i’s watersheds repeatedly granted the plantation owners leases—and later, month-to-month revocable permits—to divert Maui Hikina streams. Through such rubberstamp giveaways, plantations continued diverting streamflows from 33,000 acres of public trust Crown Lands in Honomanū, Huelo, Ke‘anae, and Nāhiku, while also skirting Hawai‘i’s environmental laws. But the people of Maui Hikina never gave in or gave up.

The Native Hawaiian Legal Corporation (NHLC), representing Nā Moku ‘Aupuni ‘o Ko‘olau Hui, an association of kalo farming ‘ohana, engaged in a 20-year legal battle against Alexander & Baldwin, Inc. (A&B). In 2001, Nā Moku petitioned the state water commission to restore flows to 27 streams and also challenged the state land board for permitting A&B’s diversions of water from state-managed Crown Lands.

Maui Hikina’s Hōnōmanu Stream completely dewatered by sugar plantation diversions in 2019

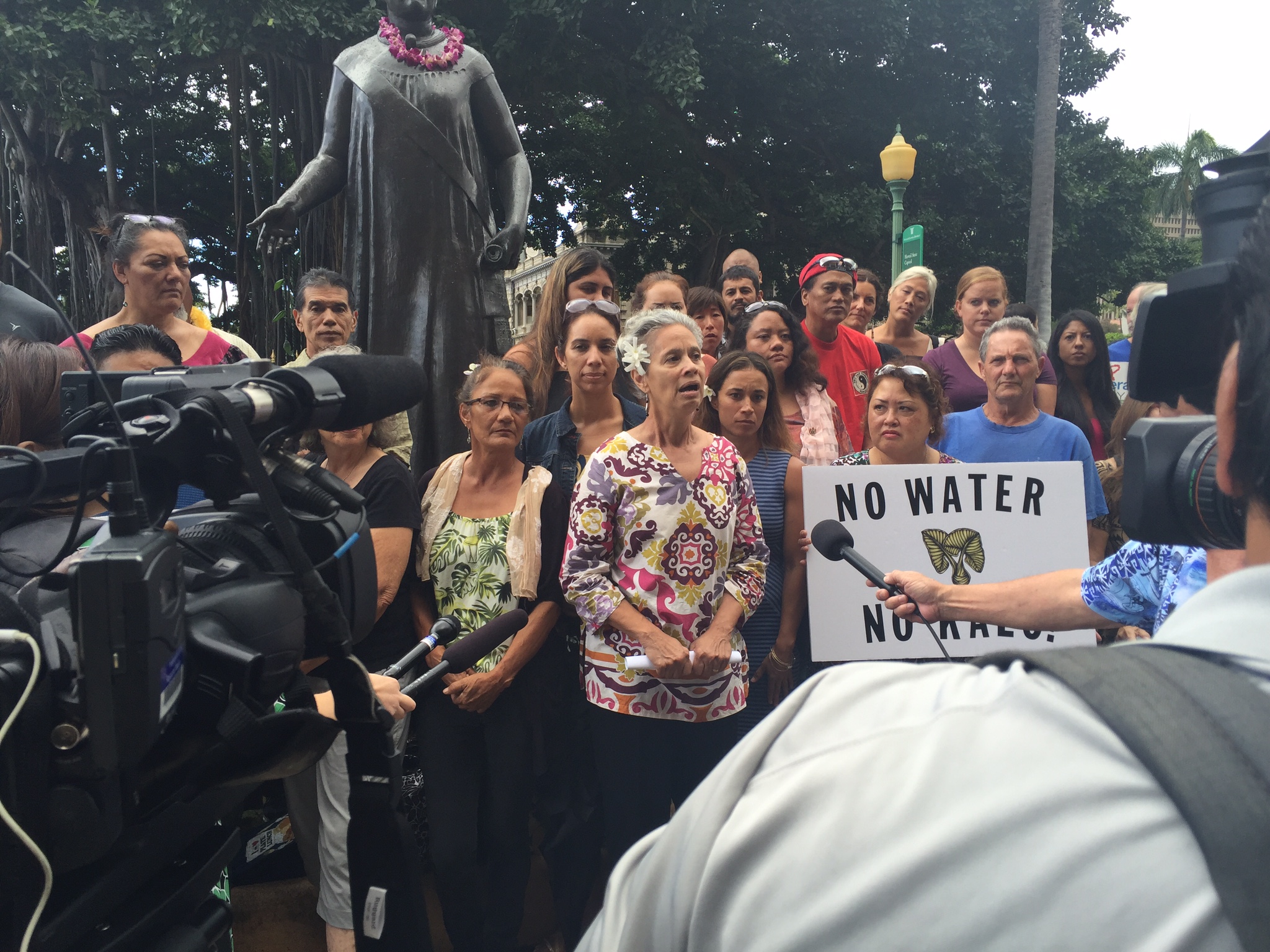

While both cases were still winding their way through the legal system, A&B used its political muscle at the legislature in 2016 to change the law to cater to A&B’s continued diversions. In 2019, a broad coalition of kalo farmers and social and environmental justice allies killed H.B.1326, a second attempted favor to A&B, signaling a pathbreaking shift in the history of land and power in Hawai’i. The water commission issued a landmark decision in 2018 restoring flows to many Maui Hikina streams. And in 2022, the Hawai‘i Supreme Court confirmed that the land board’s repeated rubberstamp approvals violated the law.

For more information about how they secured these victories, click here.

In addition to joining the coalition at the legislature, the Sierra Club of Hawai’i also brought legal action to protect an additional 13 streams in Maui Hikina that were not covered in Nā Moku’s original 2001 petition for streamflow restoration. The Club sued the land board for its practice of rubberstamping temporary permits for A&B to divert streamflows without even measuring the streams, or remedying the egregious amounts of waste, harm to downstream users, and rubbish in the streambeds. The Club also filed a new petition with the water commission to protect the additional streams.

To learn more about the twists and turns in this case, click here